The theme for Week 12 of the 2015 edition of the “52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks” challenge is “Same” and my ancestor is my 3rd great-grandfather, Ignaz Echerer. In modern times, Ignaz might be called “Junior” – for he had a lot of the same details of his life in common with his father.

Ignaz’s Story

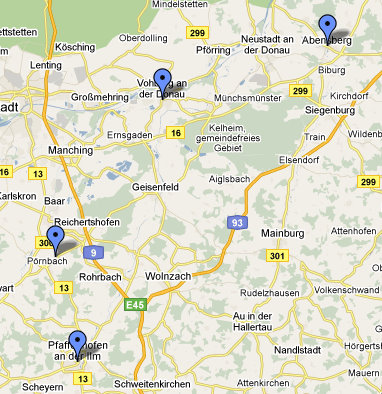

Ignaz Echerer was born on 21 Dec 1803 in Pfaffenhofen an der Ilm, Bavaria. A lot of the facts of Ignaz’s life are remarkably the same as his father, and the similarities begin at birth. First, they have the same name – both are named Ignaz Echerer. Next, they were both born in the same house in Pfaffenhofen. Today that address is called Löwenstraße 14. From 1810 to 1861, house numbers were used in lieu of numbered street addresses, so it was house #55. Prior to the official mapping of the town in 1810, the same house was known as house #67 in the 2nd quarter. But, no matter what you call it, the house was the same structure. The street (formerly called Judengasse), is located a block away from the main hauptplatz – or the town square. Ignaz (the younger) would later move in 1847 to a different house.

Portion of an 1810 map of Pfaffenhofen an der Ilm – the house of Ignaz Echerer is marked with the red arrow. The town’s church is in the lower left marked with the cross.

As most sons in 17th through early 19th century Bavaria, young Ignaz followed in the footsteps of his father – no pun intended by that phrase, for his occupation was shoemaker! It was common to run the business for the craft in the bottom floor of the house in which the family lived, so Ignaz would have grown up learning the trade – just as his father learned from his father and grandfather.

Ignaz (the younger) got married to Magdalena Nigg on 19 Feb 1844; he was 40 years old and the bride was 36. This was a common age for men to marry in that time and place, although the bride is slightly older than usual and explains why the couple did not have as many children as most couples, including Ignaz’s parents. This is one fact that is not the same as his father, for Ignaz the elder was about 31 when he got married. However, there is another marriage fact that is the same between the two men: both married a woman who was not only also from Pfaffenhofen, but both were the daughters of a different kind of craftsman. In my Bavarian research I’ve found that brides were often daughters of the same craft but from a different town. In other words, both men might have married a shoemaker’s daughter from a neighboring town. Instead, Ignaz the elder married the daughter of a glassmaker in town, and their son Ignaz married the daughter of a carpenter in town (profiled in Week #10).

The entry in the marriage index for Ignaz Echerer and Magdalena Nigg. Note the look of the name “Echerer” in German Sütterlin script.

Ignaz and Magdalena had at least three children. Unlike his father, he didn’t give his son the same name, but instead named him Karl, quite possibly after his father-in-law.

Ignaz died on 01 Feb 1874 at the age of 70. His wife lived another four years. I can’t say if Ignaz had the same life span has his father, because I haven’t found his parents’ death records. One great thing about this 52 Ancestors challenge is that I’m finding out where my research could use some additional re-search! The Echerer line in Pfaffenhofen was the very first ancestral line I “found” – but as a beginner I didn’t document my facts as well as I should have. Not to mention that those were the days before you could make a digital copy of the records you found.

Ignaz Echerer and his father has a lot of things about their lives that were the same: same name, born in the same house, born and likely died in the same town where they lived their entire lives. They were both shoemakers, and likely worked side by side in the same shop. And they both married women in the same town who were daughters of non-shoemakers. They also had many things that were different though – the elder Ignaz lost his own father when he was only 13. He also got married younger and had more children, and quite likely died in that same house in which he was born.

I wonder if their personalities were the same or if they were polar opposites?

Just the Facts

- Name: Ignaz Echerer

- Ahnentafel: #44 (my 3rd great-grandfather)

- Parents: Ignaz Echerer (1765-?) and Maria Anna Kaillinger (1768-?)

- Born: 21 Dec 1803 in Pfaffenhofen an der Ilm, Bavaria

- Siblings: Rosalia Echerer (1796-1880); Xaver Echerer (*1799); Johann Evangelist Echerer (*1802); Johann Nepomuk Echerer (*1806-aft 1842); Anton Echerer (*1808); Elizabeth Echerer (*1810); Xaver Echerer (*1812)

- Married: Magdalena Nigg (1807-1878)

- Children: Therese Echerer (*1845); Karl Echerer (*1846-aft 1882); Barbara Echerer Dichtl (*1849-aft 1894)

- Died: 01 Feb 1874 in Pfaffenhofen an der Ilm, Bavaria

- My Line of Descent: Ignaz Echerer-> Karl Echerer-> Maria Echerer Bergmeister-> Margaret Bergmeister Pointkouski-> father-> me

Written for the 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks: 2015 Edition– Week 12: Same

#52Ancestors

See all of my 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks stories on the 52 Ancestors page!