When I use prompts or themes to write with challenges such as “52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks” or the much loved but long-gone “Carnival of Genealogy,” usually I either read the theme and know immediately who or what I will write about, or it takes a great deal of thought to come up with something. This week, for Week 3 of the 2022 “52 Ancestors” theme of “Favorite Photo,” I discovered a third option: I knew exactly which photo I wanted to write about, but then it was as if another ancestor was like a child raising her hand and yelling, “Me! Me! Pick me!” When your great-great-grandmother metaphorically speaks to you, listen – as it turns out, I had already written about my “other” favorite photo in 2015, and my 2nd great grandmother’s life was quite extraordinary in simple ways. Her name was Elizabeth Smetana Miller. Her ancestors were “pioneers” of sorts, fleeing religious persecution and settling – even founding towns – in a foreign land. In her youth, her family and several others moved 90 miles away from their birthplace in search of better things. Later, as a mother, her children began to migrate even further away to the United States. I have a documented oral history from a cousin that tells even more of her story: she cared for her younger children plus five grandchildren for over a year. Then, after seeing her grandchildren and one son off to America, she faced widowhood and a world war on their doorstep. Surviving the war years, she would make one more journey – this time to America herself – where she lived another quarter century as the family matriarch in Metuchen, New Jersey. The few facts and stories tell me she was one tough cookie!

Here is my favorite photograph of Elizabeth Smetana Miller. It was taken on Long Island, NY in 1925 and she is holding her great-granddaughter Lucille. Besides wanting to tell Elizabeth’s story, I chose this as my current “favorite” photo for several reasons. I was able to see and photograph it in the summer of 2014, but I had only learned the previous year that Elizabeth immigrated to the United States. I had assumed she died in Poland and was quite excited to discover otherwise. Finding the cousin that had the photos and stories – as well as finding out about Elizabeth’s long life – was a mix of genuine research and serendipitous good luck!

Elizabeth Smetana was born on 06 April 1858 in Zelów, a town that is in Poland today. Then Poland did not exist as a country, and this area was under Russian rule. Her family, and most of the town of Zelów, had lived in the area that is now Poland for over a century, but they were ethnically Czechs from Bohemia. Her name in Czech is Alžběta Smetanová; in Polish it is Elżbieta Smietana.

She was the fifth child born to Pavel Samuel Smetana and Anna Karolina Jelinek (Jelínková). Pavel’s ancestry will be discussed later this year for another theme of “52 Ancestors” – for now let’s just say there are some questions about his parentage. But Anna’s ancestors are among the “founding fathers” of Zelów and some of the other Protestant Czech settlements that proceeded it as they were fleeing religious persecution in their homeland (read about one of her ancestors here). Both sets of Anna’s grandparents, Jan Jelinek-Maria Pospischil (Pospíšilová) and Jan Jirsak-Anna Nemecova, moved to the town within the first few years of its founding in 1802.

Zelów was founded as a farming community, but as the town grew, residents who were not landowners became weavers. Their skills led them to migrate to two larger cities that had a need for skilled textile workers: Łódź and Żyrardów. During Elizabeth’s childhood, approximately in the 1870s, at least eight Zelów families moved to Żyrardów for these opportunities.

In addition to the Smetana family, the family of Matej and Marie (Szara) Miller were among those who moved. The Miller family had a son, Jan, who was born in Zelów on 24 November 1849. He was almost a decade older than Elizabeth, but the pair were married by 1880.

Elizabeth and Jan Miller had eight children:

- Emil born on 22 December 1881

- Marya (Mary) born on 24 March 1884

- Karolina born on 12 March 1886

- Elizabeth born on 19 November 1890 (my great-grandmother)

- Paweł born on 11 December 1893

- Alfred born on 18 April 1896

- Zofie born on 03 April 1903

Their oldest son, Emil, was the first to emigrate to America in 1904, followed by his wife and daughter. Jan and Elizabeth’s daughter Elizabeth followed in 1909. In 1912, Mary, now the wife of Ludwik Szulc (Shultz), followed her husband. At the time, the Shultz’s had five children, but Mary left the children – temporarily – with her parents, Jan and Elizabeth. It is through Mary’s oldest daughter, Louise, that I know about their living arrangement. Louise was born in 1903 and was only a girl of nine when her parents left for the U.S. For a year Louise lived with her siblings, grandparents, uncles and one aunt who was the same age as her. Decades later, Louise told her story to the Ellis Island Oral History Project. [The entire story of Louise Schultz and her family is told in a 3-part series of posts beginning with Life in Poland and the Decision to Leave (Part 1); I repeat a few snippets here.]

Elizabeth was now responsible for her own four children still at home – ages 19, 16, 12, and 9, as well as her daughter Mary’s five children – ages 9, 8, 6, 4, and 3. In addition to the added responsibility of caring for five young grandchildren, Elizabeth was the sole supporter of the family because her husband Jan was sick.

Louise, like most 9-year-olds, thought her grandmother “was old, but actually she was not.” [Note: her grandmother was 55 years old at the time.] Louise explains, “My grandfather was sick; he was in bed. She was very fast, my grandmother. She worked the looms, one on one side and one on the other so she could make enough money.”

Finally, on 06 August 1913, Mary and Ludwig Schultz sent enough money for their children to immigrate, accompanied by their uncle Alfred Miller. Just three weeks later, Jan Miller passed away on 25 August, leaving Elizabeth a widow with three children still at home: Paweł, Ludwik, and Zofie. Perhaps she had hopes of joining her adult children in America, but those hopes were dashed by the “Great War.”

When the war began, Żyrardów was on the front line. Hundreds of workers were drafted into the army. Because of the decrease in workers and the lack of raw materials, the factory began to reduce production. Food prices increased. As German troops made their way through Russian Poland, martial law was declared.

In early 1915, goods, raw materials, and machines were removed from the textile factory. The town was deserted due to forced digging of trenches, general displacement, and epidemics of infectious diseases. The worst came after the collapse of the front line of Płock-Bzura-Rawka. On the night of July 16, 1915, the retreating Russian army blew up the main factory buildings. By the end of 1915, the town was under German occupation. During that time, charity committees were abolished and strict food regulation was imposed.

In an article in The New York Times on October 26, 1915 (originally printed in The Chicago Tribune on September 24), reporter James O’Donnell Bennett writes about crossing “Russian Poland” which at that time in the war was in German or Austrian control. He writes:

Often in the last five days I have made the experiment of looking out over the wide landscape to see if I could find an unscathed tract of country. Always the experiment is a failure. Always a shattered church tower notches itself against the sky or a battered village lies crumpled at the edge of fields.

The reporter mentions several towns his party traveled through, including Żyrardów. He describes the whole country as

…flyblown and sodden and a ‘nobody cares’ atmosphere envelops it…It is all waste and wreckage, wreckage and waste, a land of grime and ruin and sour smells, of silent fields and slatternly women, of weary sentries…

Louise said her aunt eventually told her what it was like during the war and “how awful it was when the German army went through the town.” Louise realized that she and her siblings “just missed the horror of a war. They used to hide in cellars and had no food. My grandmother went from one farm to another to beg for a piece of bread.”

It is believed that Elizabeth’s son Paweł was part of the Soviet roundups in Żyrardów that sent residents to Siberia. He did not return from the exile and presumably died there. Elizabeth’s daughter, Karolina Miller Razer, may have suffered the same fate; her sister Zofie later told her niece Louise that Karolina died “in prison”.

Ludwik Miller, a young teenager, either joined or was conscripted into the Russian Army sometime during the Great War. He survived the experience and lived a long life. [Although he visited the United States, he never immigrated and remained in Żyrardów.]

The oldest son, Emil Miller, who was the first of the family to immigrate to America, actually returned to Poland in 1913 after the death of his father. He brought his wife and their children, two of whom were born in America, but after the war began there was no way to leave. Emil and one of his daughters died in Poland during the war. Emil’s wife, Zofja, and American-born son Edward could finally return to America in 1927 (Edward) and 1929 (Zofja). Another daughter (Wanda) stayed behind in Żyrardów.

Widowed Elizabeth and her youngest child, Zofie, would eventually immigrate to America themselves. They sailed aboard the Megantic from Liverpool and arrived in Portland, Maine on 10 December 1920. Elizabeth a lived for a time with Alfred in New York, then with Mary in New Jersey.

I’d like to know more about Elizabeth’s life in America, but I only know where she lived and that she died on 08 November 1944 at the age of 86 (even though her obituary says 81 – I have her birth record!) Thanks to other snippets of her life gleaned through her granddaughter Louise’s memories, I think she was a brave woman. Like her forefathers before her, she also made trips in her life in search of better things. She worked hard for her family, cared for her husband, and suffered both the separation from her children and grandchildren as well as the deaths of some of her children. She also had to be of strong character to endure the suffering caused by World War 1 from 1914-1918 and continued with the Polish-Soviet War from 1918-1921. She was fortunately to be able to leave the country while it was at war.

Elizabeth was 62 when she arrived in America and she lived for another 24 years. In fact, she had a longer lifespan than her husband, probably all of her children (Ludwik’s death date is unknown, but he was alive in 1977 at age 83), and even longer than the majority of her grandchildren who grew up in relative comfort in America as compared to her life in Poland.

Sources:

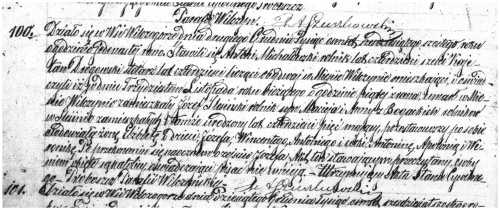

- Štěříková, Edita: Zelów (Česká exulantská obec v Polsku), published by KALICH, Prague 2002, ISBN 80-7017-793-4

- Kopie księg metrykalnych, 1826-1888. Authors: Kościół ewangelicko-reformowany. Parafja Zelów (Łask) (Main Author). Format:Manuscript/Manuscript on Film. Publication: Salt Lake City, Utah: The Genealogical Society of Utah, 1970, 1980, 1990.

- Ellis Island Oral History Project. Series AKRF, no. 0033: Interview of Louise Nagy by Dana Gumb, September 16,1985

- “Zigzagging Over Poland” by James O’Donnell Bennett, The New York Times, October 26, 1915, page 3.