Józef Pater's prisoner photo. Source: Office for Information on Former Prisoners, The State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau

Who was Józef Pater? I came upon Józef by accident while searching for my 2nd great-grandfather of the same name. I discovered that this particular Józef was my ancestor’s nephew, his brother Marcin’s son. What I learned with that search result was a forgotten story of a family – my family – who perished in the Holocaust.

If Józef’s cousins in the United States knew of his fate, it never reached the ears of their descendents. Most of what I learned about my courageous cousin came from sources written in Polish, but even those sources were limited and hard to find. The few facts I was able to piece together paint an interesting portrait of the man. Who was Józef Pater? He was an artist, a decorated soldier, a government employee, and a leader in the Polish Resistance. He was a son, brother, husband, and father. He was Catholic, and he was Polish. He died at Auschwitz. Who was Józef Pater? He was my cousin.

Józef Pater was born on 31 July 1897 in Żyrardów, Błoński powiat, Warszawske gubernia, Vistula Land, Russian Empire. He was the son of Marcin and Paulina (nee Dreksler) Pater, both 37 years old. The family moved to Częstochowa by the time Józef was in middle school. Beginning in 1914, he attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow to study painting.

As a teenager – as early as age 15 – Józef Pater became involved in politics by joining the Polish Socialist Party – Revolutionary Faction (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna – Frakcja Rewolucyjna), or PPS. The PPS was a pro-Polish independence party founded in 1892 that sought ideals such as equal rights for all citizens (regardless of race, nationality, religion and gender), a universal right to vote, freedom of speech, assembly, and press, and basic labor laws such as minimum wage, an 8-hour workday, and a ban on child labor. The “Revolutionary Faction” developed in 1906 under the leadership of Józef Piłsudski and the primary goal was to restore a democratic, independent Poland.

In November 1914, at the age of 17, Józef Pater served in the Polish Legions, a Polish armed force created in August of that year also by Józef Piłsudski. The Legions became an independent unit within the Austro-Hungarian Army. Józef Pater’s service began in the 1st Squadron of the 1st Lancer regiment in the First Brigade led by Piłsudski. In July 1916, Pater was in the 6th Infantry regiment. During these years, the Polish Legions, many of whom like Józef were citizens of Russia, took part in many battles with the Imperial Russian Army.

A short biographical sketch of Józef Pater that I found in Słownik biograficzny konspiracji Warszawskiej, 1939-1944 indicates that beginning in November 1916, he worked in boards of recruitment in Siedlce and Łuków. However, it is highly likely that Pater was part of the Polish Legions that were involved in the so-called Oath Crisis. When the Central Powers created the Kingdom of Poland on 05 November 1916, it was essentially a “puppet state” of Germany and not independent at all. In July 1917, the Central Powers demanded that the soldiers of the Polish Legions swear allegiance and obedience to Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany. Based on the example of their leader, Piłsudski, the majority of the soldiers of the 1st and 3rd Brigades of the Legions declined to make the oath. The soldiers who were citizens of Austria-Hungary were sent to the Italian front as part of the Austro-Hungarian Army, and the soldiers from the rest of occupied Poland were sent to prisoner of war camps. Since Pater is listed later in life as a member of the Association of Former Political Prisoners of the former Revolutionary Faction, it is assumed that he was one of the young soldiers interred for refusing to take the oath. Later, in 1932, he was the president of the Kutno branch of the Association of Former Ideological Prisoners.

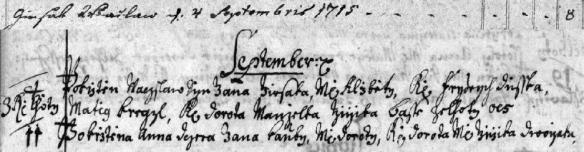

On 04 October 1917, the 20-year-old Józef Pater married Helena Feliksa Palige in All Saints Church (Wszystkich Świętych) in Warsaw.

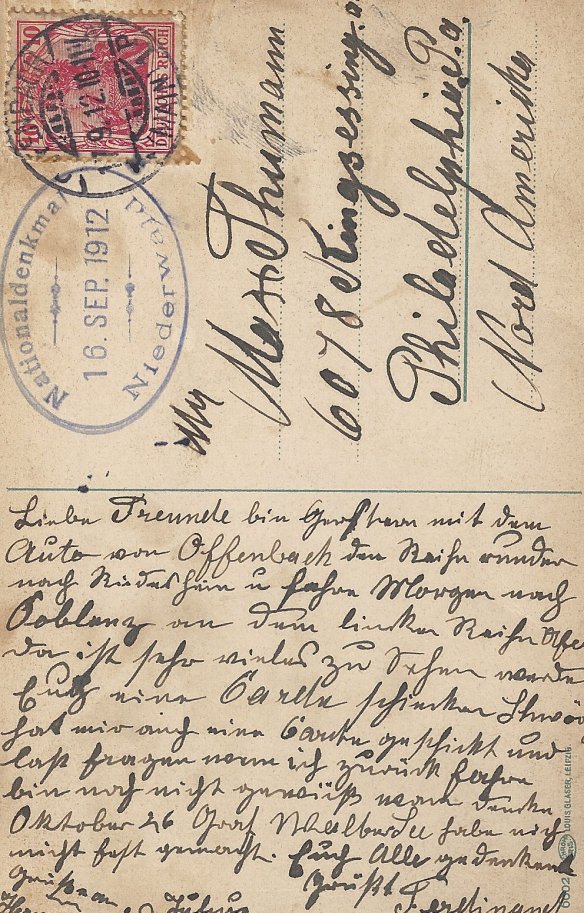

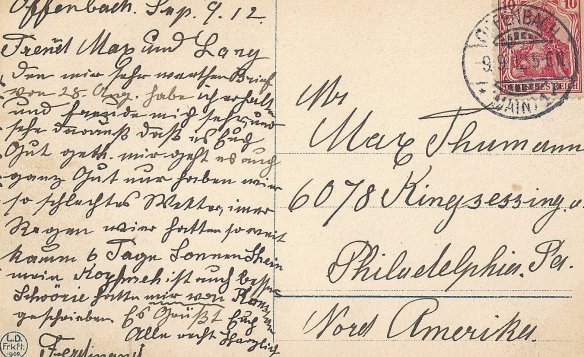

Signatures on the marriage record of Jozef Pater and Helena Palige.

From November 1918 to November 1920, Józef Pater served as a volunteer in the Polish Army. At some point he must have continued his studies at the Academy, for he was awarded a diploma in 1921 as an artist-painter. Pater rejoined the army in November 1924 and served there as non-commissioned officer in 4th air regiment. He retired from military service on 31 December 1929.

While I have little more than dates and assignments about Pater’s time in the military, I found one fact that speaks volumes: he was decorated four times with Cross of Valour and also with the Cross of Independence with Swords. The Cross of Valour is a Polish military decoration created in 1920 for one who has demonstrated deeds of valor and courage on the field of battle. Józef received the decoration the maximum amount allowed – four times. It is unknown if he received the commendation for his actions with the Legions in World War I, or if it was for any actions during the Polish-Soviet War from 1920 – 1923. The Cross of Independence is one of Poland’s highest military decorations. There are three classes, and the Cross of Independence with Swords is the rarest of the three. Developed in 1930, it was awarded to those who laid foundations for the independence of Poland before or during World War I. Józef Pater received this honor in 1931.

Józef Pater may have been a painter, but I’m not sure he ever painted for a living because following his busy military career he began to work as a clerk for the government. From 1930 to 1933 he worked in the towns of Toruń, Kutno, and Grodzisk Mazowiecki, and from January 1934 to June 1935 he worked as a clerk in the Broadcasting Agency of the Polish Radio in Warsaw. In 1935, Józef Pater became town councilor in Grodzisk Mazowiecki and he still held this position when Poland was invaded by Germany in September 1939.

The invasion by Germany was far more than a military occupation. According to Poland’s Holocaust by Tadeusz Piotrowski, the Germans attempted to remove Polish culture and way of life through closing the banks, devaluing the currency, confiscating possessions, destroying libraries, forbidding the teaching of Polish history, and banning Polish music. Himmler would announce on 15 March 1940:

“All Polish specialists will be exploited in our military-industrial complex. Later, all Poles will disappear from this world. It is imperative that the great German nation considers the elimination of all Polish people as its chief task.” (Piotrowski, 23)

Within a month of Poland’s invasion (by one source, another says a few months later), Józef Pater became the chief commanding officer (listed in narratives as having the rank of “Major”) of a Polish Resistance group called the Gwardia Obrony Narodowej (National Defense Guard) or GON. In April 1940, the GON was joined with the Związek Czyny Zbrojnego (Association of Arms) or ZCZ. This group joined with several other Resistance groups in October 1940 to establish the Konfederacja Narodu, or National Confederation – the main Polish underground organization throughout the war. The National Confederation organized a single armed force for the good of the Polish nation.

Józef Pater became one of the many leaders of the underground. From January 1941, he was in charge of police and security issues for the movement. Most participants in the Resistance movement were known to each other only by code names. Józef Pater used the names of “Inżynier” – in English, “Engineer” – as well as the name “Orlot,” which does not have a direct English translation but is a fighting eagle.

The symbol of the Polish Underground is the flag of the Armia Krajowa; the symbol on the flag is a combination of letters "P" and "W" for Polska Walcząca or Fighting Poland.

The role of the Polish Underground during the German occupation was twofold. First, they were to do everything possible to make the lives of the German military as miserable as possible. That meant sabotage, disruption of supply lines or communication, theft, damage to equipment, and similar acts. In addition to acts of destruction, the Resistance movement also sought to keep hope alive for the Polish people. Since the only authorized press was German, the Underground published and disseminated accurate information about the war to the Poles as well as getting the message out of the country. In addition, the Underground movement’s message fostered a sense of fierce pride among the Poles and offered hope that their culture and nation would survive.

On 15 February 1941, Józef Pater – and presumably his wife, Helena – were arrested in Grodzisk Mazowiecki and sent to Pawiak Prison in Warsaw. Pawiak was used by the German Gestapo for interrogations, usually brutal in nature, as well as for executions. It is estimated that at least 100,000 Catholics and Jews were sent to Pawiak – approximately 37,000 were executed there, and 60,000 were sent to various concentration camps.

In a book called Meldunek z Pawiaka I was able to learn about Józef’s character as well as the bravery of those involved in the underground movement. Franciszek Julian Znamirowski, commander of the ZCZ, became friends with Józef Pater in 1940 as co-conspirators when their two resistance organizations joined forces. Znamirowski survived the war and described Pater in a letter to author Zygmunt Śliwicki in 1970:

“The man was courageous, generous, friendly, a great patriot, the soul of a painter, and devoted to his family. He downplayed the danger. He lived in Grodzisk Mazowiecki with his family. He had a radio and listened to messages, sending them in a secret letter. At this he was caught, and we lost him. When I learned about the arrest and his confinement in the Pawiak, without much thinking I decided to move out and help him escape.”

It was rumored that Pater had typhus and was in the prison hospital, so Znamirowski obtained fake documents that identified him as a doctor of infectious diseases. Znamirowski told the guards that he was Pater’s family doctor, and he bribed them with money for entry to the prison. He described Pater as being very surprised to see him. Contrary to the rumor, he was not sick at all. He was wearing pajamas, and the two retreated to the bathroom to talk without fear of wiretaps. They talked “freely about everything” for an hour.

Znamirowski explained that he was there to help Pater escape – he believed it was possible. However, Józef’s wife, Helena, was also imprisoned there. Józef feared that if he escaped without her, there would be reprisals and she would suffer even more. He asked Znamirowski if he could return with enough money to buy their way out of the prison with the guards.

Znamirowski recalled in 1970: “He [Pater] asked urgently for help by buying him out, and it was a lot of money. We were not able to collect the cash. He was being interrogated, but he did not incriminate anybody. He held out heroically. He authorized me to take over the organization and manage it in accordance with his ideas.” It was the last time Znamirowski ever saw him.

On 17 April 1942 Józef Pater was transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Oświęcim. He was registered as Polish political prisoner and received the number 31225. He died there on 24 June.

Józef’s wife, Helena Palige Pater, was presumably arrested at the same time and also sent to Pawiak. On 22 September 1941, she was transported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp and was killed (date unknown). Ravensbrück, located in northern Germany, was known as the women’s concentration camp.

Józef’s older brother, Bronisław (born 06 September 1890), was also involved with the Resistance. On 17 January 1943 he was sent to Majdanek concentration camp and was killed (date unknown).

One source (Za Murami Pawiaka) reports that there were two sons of Józef and Helena that were also killed in the camps. Another book, Słownik biograficzny konspiracji Warszawskiej, 1939-1944, reports that one son, also named Bronisław (born 1920), was killed at Majdanek; however, there is conflicting information because there were two men named Bronisław Pater, one the brother and one the son of Józef. One of these two was transported to Majdanek on 17 January 1943 and never returned. They may have both died at that particular camp, but I lack the appropriate evidence to say for sure.

Reports differ widely on the number of deaths in the country of Poland at the hands of the Nazi regime. The commonly accepted number is six million Poles – both Catholics and Jews – died, which was roughly 17% of the total population of Poland before the war. It is estimated that of the six million Polish deaths, three million were Jewish and three million were Catholic. As the Jewish population of Poland was much smaller, Germany killed about 85% of Poland’s Jewish population and about 10% of Poland’s Catholic population.

Józef, Bronisław, Helena, Bronisław. Their names were forgotten in my family. May we never forget them again.

###

The brothers Józef and Bronisław Pater are first cousins of my great-grandfather, Louis (Ludwik) Pater and his brothers (Wacław, Stefan) and sisters (Franciszka, Ewa, Wiktoria). Louis’ father, also Józef Pater, is Józef’s uncle and a brother to his father, Marcin Pater. My ancestor Józef immigrated to America in 1905. His nephews would have been 15 and 7 years old at that time. My great-grandfather Louis did not leave Poland until August, 1907, and he was living with his adult sister, Franciszka. Given that Franciszka married Paweł Niedzinski (Nieginski) in Częstochowa in June, 1906, it is likely that both branches of the Pater family left Żyrardów and were living in Częstochowa together. Louis/Ludwik was nearly 14 years old when he left Poland; cousin Józef was 10 and Bronisław was 17.

This post has literally been a couple of years in the making. I had help with some initial research by footnoteMaven, and I would not have known much without some translations by Maciej Róg. I was further assisted with both research and translations by Matthew Bielawa . Their help is greatly appreciated!

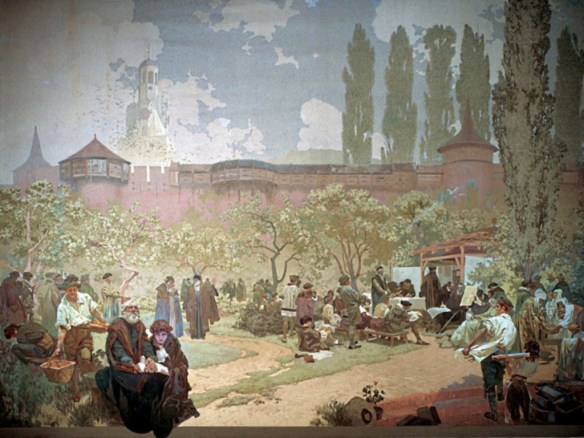

Source: Ilustrowany Przewodniak Po Polsce Podziemnej, 1939-1945

Sources used for this post:

Vital Records:

Parafia Matki Bożej Pocieszenia (Żyrardów, Błoński, Warszawske, Vistula Land, Russian Empire), “Akta urodzeń, małżeństw, zgonów 1897 [Records of Births, Marriages, Deaths 1897],” page 160, entry 637, Józef Pater, 31 Jul 1897; digital images from Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych, http://metryki.genealodzy.pl, Archiwum Państwowe m. st. Warszawy, Oddział w Grodzisku Maz. (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/metryka.php?zs=1265d&sy=134&kt=1&skan=0635-0638.jpg)

Parafia Wszystkich Świętych (Warszawa, Warszawaske, Regency Kingdom of Poland), “Akta małżeństw 1917 [Records of Marriages 1917],” page 67, entry 133, Józef Pater and Helena Feliksa Palige, 04 Oct 1917; digital images from Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych, http://metryki.genealodzy.pl, Księgi metrykalne parafii rzymskokatolickiej Wszystkich Świętych w Warszawie (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/metryka.php?zs=9264d&sy=341&kt=1&skan=133.jpg)

Death record 12625/1942, Józef Pater, 24 June 1942. Biuro informacji o byłych więźniach, Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau (Office for Information on Former Prisoners, The State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau)

Books:

Dębski, Jerzy and State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Death Books from Auschwitz: Remnants. München : K.G. Saur, 1995.

Kunert, Andrzej Krysztof. Ilustrowany Przewodniak Po Polsce Podziemnej, 1939-1945. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1996.

Kunert, Andrzej Krysztof. Słownik Biograficzny Konspiracji Warszawskiej, 1939-1944. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy PAX, 1987.

Lukas, Richard C. Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation 1939-1944. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

Lukas, Richard C. Forgotten Survivors: Polish Christians Remember the Nazi Occupation. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Piotrowski, Tadeusz. Poland’s Holocaust. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1998.

Wanat, Leon. Za Murami Pawiaka. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1972.