This 3-part series of posts uses my cousin’s interview in 1985 with the Ellis Island Oral History Project. Part 1 tells the story of Ludwig and Mary Schultz, who came to America in 1912 and temporarily left their five children with Mary’s parents. In today’s post, Part 2, their daughter, Louise, discusses living with her grandparents and the eventual journey across the ocean to join their parents.

Crossing the Border

When Ludwig and Mary finally earned enough money to reunite with their children, their young Uncle Alfred was to be their guardian throughout the journey. Louise explains,

“My uncle, he was the ‘main cheese’ in the whole thing. He was like our father, mother, the whole thing – everything rolled into one. And he spoke for us, to whomever he had to speak, for everything.”

Uncle Alfred was seventeen years old! His older sister, my great-grandmother, immigrated alone four years earlier at the age of 18. Somehow I think her trip was much easier.

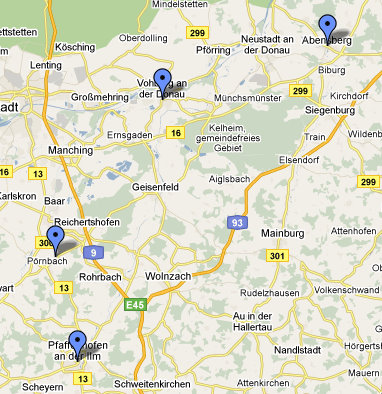

Louise explains that they all needed passports to travel, and they were expensive. They were purchased on what she calls “the black market” and “the underground” in order to get across the border from Poland to Germany, “because we had to get to Hamburg to get the ship.” They left after midnight, “in the black of night.” Louise remembered crossing a “narrow little bridge” over water. Even though she was the oldest at 10 years old, she became afraid. Uncle Alfred carried the children over one by one, depositing them on the other side, in order to get them all across.

Louise describes having very little with them:

“You didn’t have matching luggage or anything like that. You just took a sheet or something, a rag, and you folded your belongings and you tied it in the four corners.”

Their most important belongings went into a wicker basket. However, as the family was crossing the border, Alfred was told to leave the meager baggage with someone who would take it to the port where they could pick it up. When Alfred went to retrieve it with a claim ticket, but their baggage was not there. Louise remembers that he “went two or three times, then he gave up, very down-hearted.” The unscrupulous man had stolen their belongings! “It didn’t only happen to us,” she said, “it happened to many families.”

What made this situation more difficult is that the youngest, Julia, was only 3 and still needed diapers. Louise had primarily responsibility for her little sister while Alfred cared for the three boys, and it was difficult to care for her without a change of clothes.

Journey by Ship

Louise’s (Ludwika Kazimira) Inspection Card

The party of six managed to travel to the port of Hamburg, over 500 miles away, and boarded the S.S. Amerika on 06 August 1913.

The S.S. Amerika on the Hamburg-American Line

Once aboard the ship, the journey was even more difficult. They all suffered from “sea sickness, constantly.” She describes the ship’s steerage compartment as being “one big floor of everybody. There was men, women, children; all languages, all nationalities.” Cups were given out, one per person. “But they didn’t give us enough. So in the nighttime, my brother would creep under somebody’s bunk and get extra cups.”

Louise said that every morning a man would yell, “Rouse, rouse, rouse” and they would have to quickly get out. “Everybody was like soldiers in the army. You had to get out that time and just go up on deck.” She thinks they would clean or sanitize the steerage floor at this time to prevent an outbreak of disease among the passengers.

Breakfast was served. “In the morning you got coffee. There was no such thing as children getting something different, that’s all you got. It was coffee, and Russian black bread or some kind of rolls.” At dinner, “we sat at these long tables, everybody together. We got a herring thrown on the plate and boiled potatoes.”

Arrival at Ellis Island

They finally arrived in New York City on 17 August. Louise remembers taking a ferry from the ship to Ellis Island. She explained,

“My parents came to pick us up the same day the ship landed. However, our name was Schultz, and my uncle’s name was Miller. I think we went under his name because he was the adult. When my parents came to pick us up, my father told the names. They said there’s no Schultz, he couldn’t find it. And my father didn’t believe them. He argued back and forth, but they couldn’t help him out. So they went home and they came back the next day. That means we had to spend a whole night there [at Ellis Island] and it was very scary to me.”

The family’s names listed on the passenger arrival record

Before they realized they were to be detained, they were processed through and had medical examinations. Louise remembered,

“They would examine your eyes, your chest, and your body in general, to see if you were healthy enough to come here if you didn’t have any contagious diseases. Consumption was a horror word, and I remember one man in particular – he must have been found consumptive and I remember him crying because he had to go back and couldn’t come into this country.”

In the Great Hall, “there were very few seats. It was so packed that you were almost standing close together. And I remember it was in August; it was very hot.” The hall “had such a resonance, the sound, the acoustics.” Several times a day a man would go up on a platform and call out names, which mean that someone was there to pick you up and you were allowed to leave. “And we waited and waited, we went each time they were calling the names.”

The Great Hall at Ellis Island – taken by the author on August 7, 2010

They continued to wait for their parents. After names were called, “everybody dispersed, just sat around or walked around waiting for the next call. And then it was night time and there were long tables for eating a little supper. I don’t remember the meals too much; the only thing I remember is that it was the very first time in our lives that we had slices of white bread. In Russia it was black bread!”

The doctors performing the examinations wore “white coats” but the other officials at Ellis Island wore uniforms. Louise thought they looked “like conductors on the street cars with peaked hats” and navy blue uniforms. They were “very abrupt, very short” and wanted everyone to “move, move, go, go, come.”

On 18 August, a presumably anxious Ludwig and Mary returned to collect their children. Louise said her father “went home very upset” that first day and “he didn’t know what to make of it.” The next morning, he returned and “made the official let him look at the book.” The official let him see the list, and he quickly found the names for his brother-in-law, Alfred Miller, and the five Schultz children. Louise remembers that they had to go outside, and a chain-linked fence separated the new immigrants from the family members that came to pick them up. “We had to identify each other,” Louise remembered,

“Now, I was the oldest, and the younger children did not know my parents. My mother had gotten stouter; she was a slim lady when she left us. And my father changed. So I had a rough time, but I had to say ‘Yes, that’s my father and that’s my mother’ and we finally went through the gates. That was it, we were finally in this country!”

In Part 3, we will learn more about what life was like for the family in America — and what life was like for the family they left behind in Poland.

A recurring theme on this site is my desire to find photographs of my ancestors because I have so few. I even entitled one post about Elizabeth “

A recurring theme on this site is my desire to find photographs of my ancestors because I have so few. I even entitled one post about Elizabeth “

I finally took my own journey to Ellis Island in the summer of 2010 with five genealogist friends. It was a wonderful experience. I was surprised the “Great Hall” was not quite as large as it looks in photographs. What made our trip meaningful was that all of us had ancestors who arrived through that port and the realization that their fateful decision to come here shaped our own lives.

I finally took my own journey to Ellis Island in the summer of 2010 with five genealogist friends. It was a wonderful experience. I was surprised the “Great Hall” was not quite as large as it looks in photographs. What made our trip meaningful was that all of us had ancestors who arrived through that port and the realization that their fateful decision to come here shaped our own lives.

This week I am highlighting some random facts about passenger lists. Today’s post won’t offer any helpful searching hints or useful sites. Instead, let’s journey down memory lane to the good old days before we did our research on the internet. Wait, why exactly do we call them the good old days?

This week I am highlighting some random facts about passenger lists. Today’s post won’t offer any helpful searching hints or useful sites. Instead, let’s journey down memory lane to the good old days before we did our research on the internet. Wait, why exactly do we call them the good old days?

I noticed that the manifest had a big “X” next to her line number. That is a signal that the passenger was detained for some reason, and there may be more information available. For more information, see

I noticed that the manifest had a big “X” next to her line number. That is a signal that the passenger was detained for some reason, and there may be more information available. For more information, see