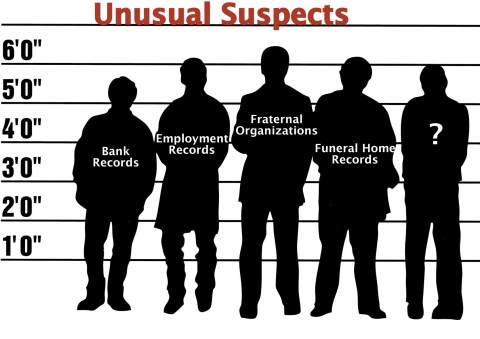

Continuing the Family History through the Alphabet series… O is for Occupations! Some of the many interesting things I’ve learned while researching my family history are my ancestors’ occupations. What skills, trades, and talents are on your family tree?

Continuing the Family History through the Alphabet series… O is for Occupations! Some of the many interesting things I’ve learned while researching my family history are my ancestors’ occupations. What skills, trades, and talents are on your family tree?

I’ve written about my family’s occupations in the past, so for today’s post I’m taking a different approach to the topic of working for a living. Has your own choice of a job or a particular talent been unknowingly influenced by your ancestors?

On the episode of Henry Louis Gates’ Finding Your Roots featuring Martha Stewart, Dr. Gates seemed surprised to discover that many of Martha’s ancestors’ jobs involved such decorative arts as basket-making, iron work, and gardening. These crafts have also played a role in Stewart’s career as a decorator. But when she embarked on that career, she knew nothing of her family’s history in similar fields.

I was not as surprised as Dr. Gates because I have experienced exactly the same thing in my own family history research when comparing some of my ancestors’ occupations to that of my brother and myself.

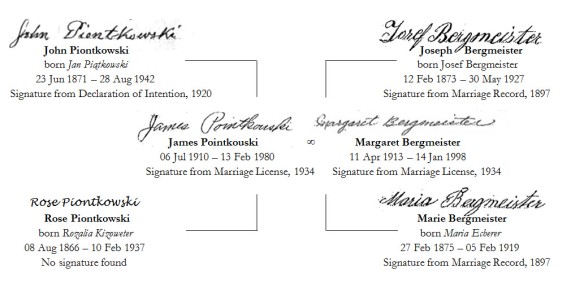

My brother has some similarities to our great-grandfather, Joseph Bergmeister. Joseph’s primary occupation in life was a baker – my brother is not. However, we found a curious connection in another earlier occupation of Joseph’s. During his mandatory military service in the Bavarian Army, Joseph served in the Leib Regiment, or the Königlich Bayerisches Infanterie Leib Regiment. This roughly translates to the Royal Bavarian Infantry Life Guard Regiment. This elite regiment protected the royal family, and was headquartered in Munich at the royal palace. Our great-grandfather served in this unit from 1893-95 when he was only 20 to 22 years old.

When my brother was 21 years old, he joined the United States Marine Corps, another elite branch of the military known for their rigorous training and “spit and polish” image, much like the Leib Regiment. While in the Marines, my brother served as an Embassy security guard, which would have had similarities to the Leib Regiment not only in function – as a protection and security unit – but also in form in terms of strict protocol and image.

While these two military jobs were similar, my brother’s later career mirrored Joseph’s Leib Regiment service even more closely. Years later, my brother served in the state police. His time in service included working on the executive protection detail guarding the governor. Coincidentally, the uniform of the Leib Regiment and the state police have one remarkable similarity – they coat/shirt of each uniform are a bright light blue.

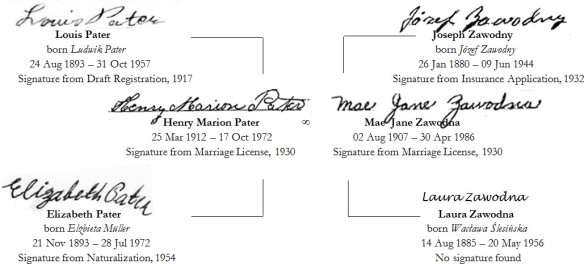

As for my own career, I’ve spent the last twenty years as a “civil servant”. I was surprised to discover that the career I stumbled upon by accident is closely interwoven with the careers of multiple ancestors. None were civil servants, but their jobs instead are directly related to the industry that I’ve worked with in my government job – the U.S. clothing, textile, and footwear industry. I’ve worked with this shrinking domestic industry, one that is nearly entirely dependent upon the military, for my entire career.

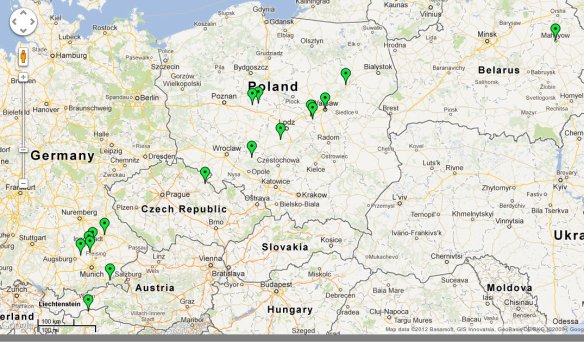

When I first started my job in 1992, I knew that my maternal grandparents had worked in the textile factories that once populated Philadelphia. But after that, as I spent more spare time researching my genealogy, I began to uncover more generations involved with this industry – a whole collection of weavers, seamstresses, cloth merchants, and shoemakers! Some of these occupations are on both my father’s and mother’s side of the family tree including generations of both Bavarian and Polish shoemakers. My maternal grandfather’s family, all weavers, came from Żyrardów, Poland – a town founded to produce textiles. It soon became the largest textile-producing town in the entire Russian Empire by the end of the 19th Century. I may not weave fabric or make clothes or shoes myself, but thanks to my desk job I know more about these industries than I ever thought possible.

I wondered about other occupational connections in the family. My father worked as an accountant, and while I haven’t found any bean counters in his family’s history, I realized that in his younger days he was quite talented at construction-type jobs around the house. Did that talent stem from his Bavarian carpenter and mason ancestors? My mother also worked as a bookkeeper and a bank teller, but her dream job, and her talent, was designing and making clothes. Did that passion come from her weaving ancestors?

Perhaps we have a genetic memory within us that calls us to certain occupations or pastimes. I’d like to think so, but then again maybe it’s just a matter of some remarkable coincidences. I’d like to know who the historian in the family was… Because I think I inherited that gene!

[Written for the weekly Family History through the Alphabet Challenge]

[Written for the weekly Family History through the Alphabet Challenge]

[Written for the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge]

[Written for the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge]

Continuing the

Continuing the